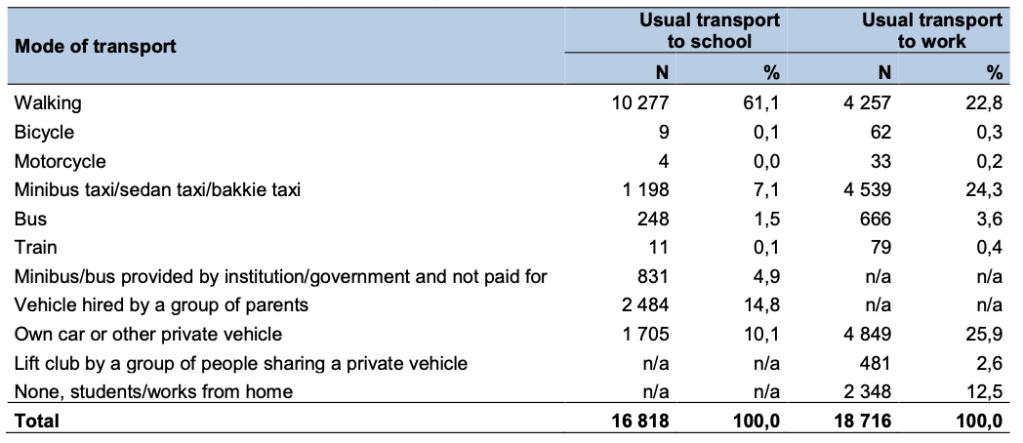

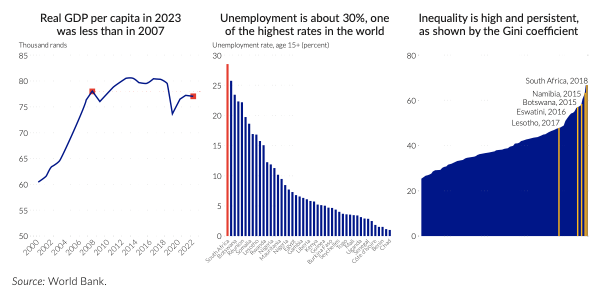

This week, the General Household Survey (N=35535) reinforces the the notion that commuters either travel via private car (25.9%), use minibus taxis (24.3%) or walk (22.8%) to work, shown below. The most recent CPI data, shows how households spend 14% of their income on Minibus Taxi fares, the second largest expense to Fuel (purchased by all vehicle owners). The World Bank reveals the deeply rooted and compounded cost of passenger transport inefficiencies which result in households spending as much as 80% of their income on public passenger transport. This constitutes a crisis in the passenger transport sector, as households are excluded and poverty, inequality and unemployment are reinforced by a lack of affordable, efficient and effective mobility and access.

“Addressing economic exclusion in South African cities, which remains important even 30 years after the end of apartheid, requires improving mobility and reducing distance through more efficient and equitable transport services and improving urban development. While economic exclusion results from multiple factors, many studies have demonstrated that urban workers’ limited and costly mobility (accounting for about two-thirds of the labor force) is key in South Africa. On average, typical workers could spend about half of their earnings on transport (up to 80% for the poorest), compared with 10% in Vietnam.“

World Bank, 2025

Much of the critical interventions are framed within the context of network industries, particularly rail transport, however, I argue that this may not level South Africa from the tipping point.

In 2020 National Treasury published a bold policy paper titled “Economic transformation, inclusive growth, and competitiveness“. This was under the late Finance Minister Tito Mboweni. The policy paper was an economic strategy which framed the reforms in network industries, particularly railways, electricity and telecommunications. It is at the heart of overcoming overcome structural limitations in the South African economy, today. This note, untangles these reforms and highlights the urgent need to expand them to the road based passenger transport sector in crisis.

Railway reform as an instrument for economic prosperity

The underlying constraint with railways as a network industry is that it was initially intended for resource extraction in Africa. This aim was focused towards capital outlays of fixed lines, ports and other infrastructure designed to export minerals out of Africa. Today, Afriximbank found that a 1% improvement in the quality of ports is estimated to increase intra-regional trade by 32.5%, while railways do not seem to contribute significantly to intra-regional capital circulation.

This embedded constraint is tackled by the African Union Agenda 63 flagship project for a high-speed rail network to enable regional integration. However, when distilled from an access to capital perspective, the disproportionately higher cost of finance in Africa spills over to the prospects of achieving this. Public and private sector efforts are encouraging, but they should be complemented by a basket of reforms. For household income effects to surface, industry policy which orientates the spatial configuration of African settlements, communities and cities is critical. In order to achieve this broader economic strategy, labour is a critical input for its operationalisation– this includes where people work, live and how they commute.

South Africa’s economic reforms strategy can be described through operational, tactical and strategic levels. The Railway Reform framework by the World Bank highlights that reforms require changes in policy, institutions and management.

- The strategic policy interventions include the Rail Policy of South Africa. They also involve the recently published Network Statement to liberalise network access. Additionally, there are Public Private Partnership reforms.

- Tactical institutional changes include the formation of the Interim Rail Economic Regulatory Capacity (IRERC), and the National Logistics Crisis Committee.

- Operational management changes include business changes at Transnet, such as executive restructuring. They also include improvements in ports, terminals, and railway operations in the freight sector.

While the overarching reforms are critical in the macroeconomy, there remains deeply rooted constraints to circulating returns on structural efficiencies and household income multipliers. One of the contributing factors is the underlying friction between the efficiency of railways, logistics surrounding them, and the workers who are managed to implement business and development targets. This friction is caused by what we in the transport science environment call “impedance” as a function of the cost of reaching a destination to derive a certain value from a point in space and time (see Transport Geography Book). As a result, when commuters face long travel distances, time, and high costs of transportation this dilutes the benefits of job creation and increased household income through industrialisation, capital investment or other impacts of such reforms. There is no clear policy reform to address this, other than the Operation Vulindlela Phase 2, which proposes a specific focus on spatial transformation. Overcoming spatial inequality is a pivotal step to enabling a fluidity between capital returns and income circulation among households– improving the income multiplier effect from investments.

Spatial inequality as an economic constraint for structural reforms

In South Africa the impedance from a mobility and access perspective is exacerbated by spatial inequality, or what we call today “Apartheid Spatial Planning” which was historically incentivised by economic policy. The structural economic foundation of the Republic was such that African natives would be morphed into minerals mined by economic and industrial policy first. Only through this extractive approach to labour was the anthropological framework for spatial displacement developed and incentivised. Methodically investigating the impact of spatial inequality and its incentivised form within the context of railways and industrial policy can quickly reveal a systemic reinforcement of spatial inequality over time– at the cost of commuters.

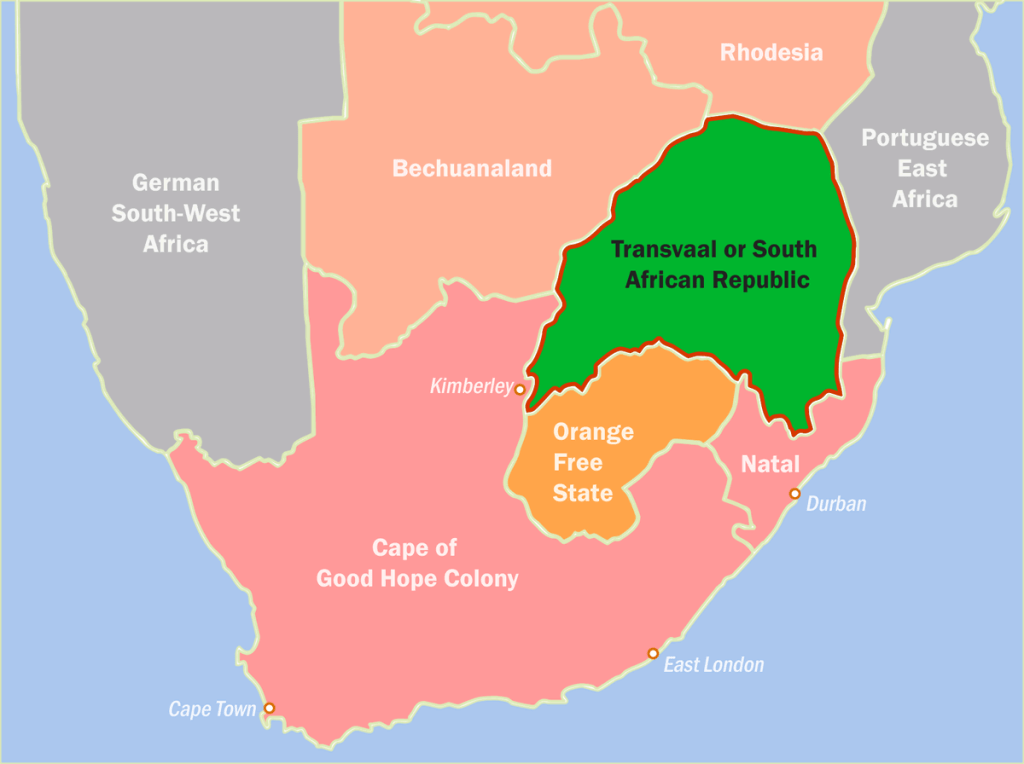

The economic framework to incentivise this exponential reinforcement over 100 years, begins in the colonisation of South Africa, then formalised through the Union of South Africa and finally established during Apartheid. Divided by settlers since 1652 South Africa as we know it was a series of colonies split between the South African Republic or later known as the Transvaal (Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga), Cape Colony Government (Western Cape, Norther Cape, Eastern Cape), Orange Free State (Free State), Natal, Zulu Land (Kwa-Zulu Natal) and various other settlements. Each with ethnic concentrations among African natives and settler populations ranging from Britain, Netherlands and other settlers. With these partitions, extracting minerals for exports to mother countries encountered structural and political hurdles as railways from the inland and coasts needed to negotiate terms for seamless extraction. As the docks shored a new era of government, The Union of South Africa Act 1909 set the stage for a Republic that would overcome colonial borders and settlements for the seamless extraction of resources.

From a transport economic perspective, it appears that the Union of South Africa introduced a policy framing for agricultural and industrial developments by reducing the impedance (cheap transport):

“The railways, ports, and harbours of the Union shall be administered on business principles, due regard being had to agricultural and industrial development within the Union and promotion, by means of cheap transport, of the settlement of an agricultural and industrial population in the inland portions of all provinces of the Union.” – Union of South Africa Act 1909

This resulted in a policy instrument which priced railway markets at what the traffic can bear initially for freight transportation. It implied that freight operators could only charge what farmers, and industrialists could afford and the Union would subsidise the difference. The industrial incentives were the most compelling, accelerating economic development at a rapid rate and therefore Manufacturing Apartheid.

As the policy evolved over 20 to 30 years, passenger transport was included, however both the public and private sector were needed to incentivize a growing population of Black Africans.

Industrializing spatial equality as a key lever to accelerate inclusive growth

The political economic framework underpinning modern rail and road passenger transport services sets a dire scene for a deregulated market. The deregulation of road transport in 1970 gave birth to the 400 000 minibus taxi and large road freight industry we see today. I would like to tally the period before deregulation to outline the manner in which “what the traffic can bear” as a policy principle permeated through land-use, available modes and mode choice. City Johannesburg, a poem by Mongane Wally Serote paints a salutation that strokes through its urban turmoil of race, hunger, technology and distance weighing heavily over human life. He tells a tale of a City in 1971 that inhales labour from the fringes and exhales gold, iron, copper, and coal along production lines separating whites from blacks swiveling on the tarmac. Jeremy Cronin describes the marginalization and containment of black Africans as a reality “planned under apartheid” and “has often been unintentionally perpetuated”. However, there is no clear research which connects the political economic framework incentivizing the marginalization and containment into perpetuity.

A fundemental cause of apartheid spatial planning is the public transport subsidization mechanisms that were in place between 1910 and 1970. Gordon Pirie’s work is perhaps the most detailed collection of arguments which link spatial segregation with railways since 1918, wherein railway infrastructure decisions were made based on segregated settlement planning — not economic viability of the lines. This hard-wired a spatial form which was accelerated by land-use planning policies such as the Group Areas Act of 1930. Therefore, transport infrastructure became the backbone of spatial segregation. Once the automotive industry emerged, road infrastructure, sprawling suburbs and buses became a necessity because the capital outlay for rail would be too high. Meshack Khoza details an array of subsidy reforms from the temporary bus subsidies in the 1940’s to subsidies from industries and employers which became a prominent feature to ensure that public transport remains affordable for the displaced and marginalized workers. While subsidy reforms have emerged over the years, Jackie Walters describes the extent to which government can not effectively afford the current and future bus subsidies. Whereas, the passenger railways have not been able to remain competitive as spatial change, sprawling townships and increasing urbanization has resulted in inefficient train station location or the urgent need for cities to control and manage railway services more efficiently.

At the crux of it, without the incentives and subsidies which set the stage for the current hardware of rail and road transport networks, it is unlikely that spatial change could occur. The deep links between industrial development, townships and fixed transport infrastructure investments framed the political economy of mobility and access squarely in the domain of industrialization. A policy moment which demonstrated the divorce between policy intent and outcomes can be found in the Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP). Initially intended to be an instrument to empower citizens to self-determination through the ownership of assets, access to basic needs and reforms in municipal service delivery. The program evolved into a subsidized housing scheme disconnected from transport, industrial and economic development patterns which would have overcome apartheid spatial planning. In the context of industrialization, a critical initiative is the Special Economic Zoning (SEZ) frameworks. A deeper look into how SEZs are connected to human settlements and transport networks for a future state of cities is the most revealing. While outlined in policy, the implementation and incentives do not necessarily echo the need for spatial transformation.

Does South Africa reside on the tipping point of a passenger transport crisis?

The combined effects of the RDP and SEZ for instance is inherently perpetuated township and urban sprawl. Today, the Fuel Levy is the core instrument for funding roads and transport, there are symptoms that it is an inefficient source of funding for the transport sector in general. This is evident in the inefficiencies of the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa’s operations and services in the past 20 years, collapsing due to severe mismanagement, poor capital planning and inconsistencies between spatial, industrial and fixed-line planning (see a note here). Accelerated by road freight and car ownership rising to a total of over 10 million vehicles — road infrastructure funding has become unaffordable, and inefficient.

There is a tipping point to a lack of modal integration in passenger and freight transport sectors. While the National Logistics Crisis Committee enables critical reforms in operations; and policy changes liberalize railways– these enable industrial efficiency. Whereas, seeing that spatial transformation is on the Presidential Agenda, there remains a need for a structural shift in policy, planning and implementation in the passenger transport sector in particular. Matching the industrial development and spatial transformation needs requires a mixture of structural interventions in the passenger transport economy at the core. The National Public Transport Subsidy Policy is a bold attempt to propose a structural shift in how the passenger transport subsidy ecosystem will be used to reinforce a self-sustaining fly-wheel through appropriate planning.

The accumulation of high household transport costs, inefficient infrastructure and poor land-use planning over the last 100 years, seem to entrench inequality and poverty (see the figure above). It remains unclear if we truly are at the tipping point or have been hovering around it to such an extent that it is a policy norm for a passenger transport sector in crisis. To determine a concrete answer to this policy challenge requires a critical assessment of the role which passenger transport plays as both a network industry and an enabler to the industries described in the Structural Economic Reforms.

[END]

Leave a comment