Across the African continent commuters have severely low expectations for public transport. A recent documentary discusses the TOT system in Accra, Ghana where commuters are charged multiple times along the journey. In Nairobi, Kenya there has been a spike in bus accidents and increased dissatisfaction with the services. In Johannesburg, commuters are taking to social media to express their frustration with popular transport services such as minibus taxis. Yet, these modes are the popular dominant form of public transport.

Every customer is a coach

Every customer is a coach. Organisations and institutions are coached by every passenger in a flight, every bus driver, and every by stander. Someone has something to say, a point of view about the experience of commuting through a congested freeway or crossing rivers to get to school.

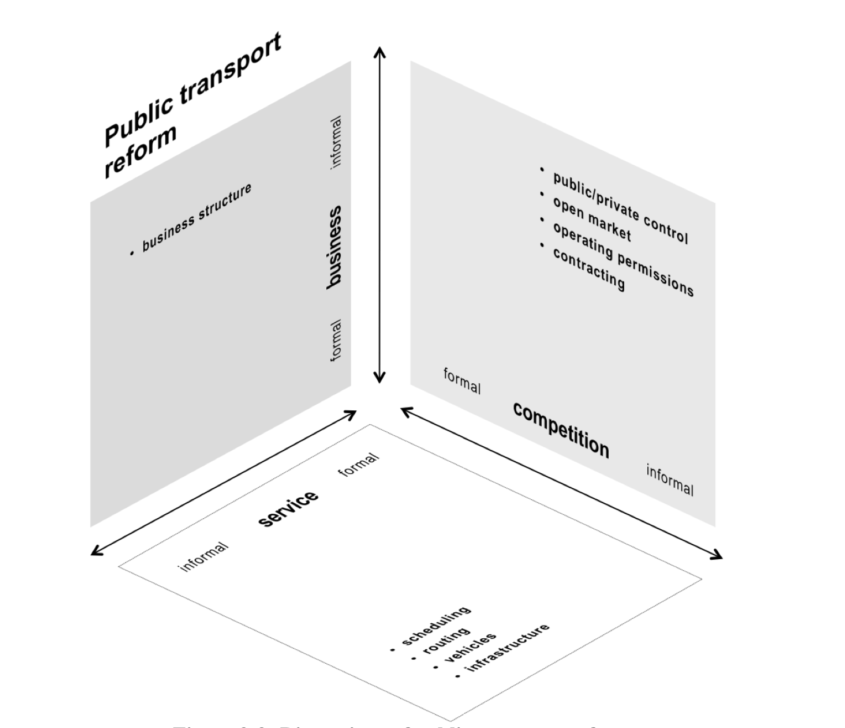

Communities grasp the value scholar bus subsidies as aging buses plough through gravel. The over crowding covered in January news cycles rolls over to year round accidents involving vulnerable users. There is a matrix of decisions which frame the outcomes chained to predictable tragedies. However, if captive users remain unheard, they will likely be imprisoned by fault lines drawn about them— without them. Hence it is ever more important now to outline the fundamentals of public transport reform in the African context as a leap to expanding access to options.

What do captive commuters know?

Customers have a degree of expertise in the products they use, love, and sometimes to hate. It’s not the poor quality experiences that keep them coming back, sometimes they don’t have a choice but to keep using the same product or service. They see the service in its formal and informal sense. In many cases, shared transport commuter experiences straddle between formal and informal realms. Personal or operational schedules may change, and the market needs to adapt; traffic circumstances may demand a change in route— or the days plans require a modified trip journey. Vehicles may or may not be ideal for the use case but are accustomed to providing the services. Infrastructure for the particular mode choice may exist, or be augmented to fill a usage gap resulting in traffic light skipping, informal bus stops, ranks and holding areas. Customers are well adapted to these nuances, and fluent in their lexicon as a norm, and captive commuters take use what is available. The role of planners, public and private sector is to enable what is feasible and not constrain possibilities.

Freedom of choice must be an option

Customers express themselves by being able to choose products and services they prefer— regulators must be passionate about ensuring this freedom of choice. Businesses need room to become agile or they lose their incentives to compete. However, regulators are typically constricted by social contracts, administrative processes and ideological differences. Whereas empirical evidence regarding economic regulation offer a basket of tools allowing users and operators great flexibility. When the do have options, they move between them and there is greater value in options than a market without them (see VTPI research on “Option Value” in a multimodal CBA context).

When freedom of choice is an option, customers become coaches, training the market to respond to their needs. At the end of the day, a great coach is a person that has high expectations, is willing to develop a team and play a fair game. Customer satisfaction is defined by whether organisations wait for the next best complaint or find opportunities to show up, and show out. This is the basis of public transport reform.

Captive commuters can’t say, hey: could you do better next time? Instead, most customers who use public transport services succumb to a numbing choicelessness that is uninspiring.

When is a customer a coach?

There is what we can call a service spectrum and a service window. A service spectrum is what customers get, the window is what they want. In the spectrum different levels of service exist for unique attributes. Service windows however, can either be large – low expectations; or small – high expectations. The interaction between the two is what turns a customer into a client. That loyal, I want to do this, personality. The client becomes the coach when they appreciate the spectrum of the services they love, and want to help the providers match the service windows they enjoy.

It takes a heartfelt experience, good and bad, to bring clients who become coaches. A simple condition needs to be met: how the service provider responds turns the client into a coach. If the taxi association keeps pushing ahead, even after the student group asked for collections at residences – they may not lose these clients today. And they will lose coaches tomorrow. Airlines neglect the 3-sized families that want to match bookings, sit together and keep their infant from being distruptive – they may not lose the family as a client. And they will lose coaches tomorrow.

A customer is a coach when both the service offering and the customer can host each other in a healthy conversation. This in my opinion, transforms a customer into a client— a meaningful business stakeholder. Not trolling, not banging at the storefront, not hello-petering: just a space to converge in conversation. The question is, who is willing to have that conversation to give radical feedback? It is through such a dialogue that the service is evaluated deeply, competition is untangled clearly and businesses have room to unlock critical reforms.

END

Thank you visiting the page. Weekly commentary shores up on Transport Tuesdays at 09:00 SAST.

Leave a comment